How to Remember Everything

Memory

Have you ever tried to remember specifics about an article or book you’ve read, and your brain comes up empty? You might know how it made you feel or if it was good overall, but the takeaways are lost. You’ve probably resonated with the old saying: if you don’t use it, you lose it.

Here in this post, I’ll try to:

- Convince you remembering things you learn is useful and important

- Give you practical steps to remember information better over time

- Invite you to share what you know to help you and others

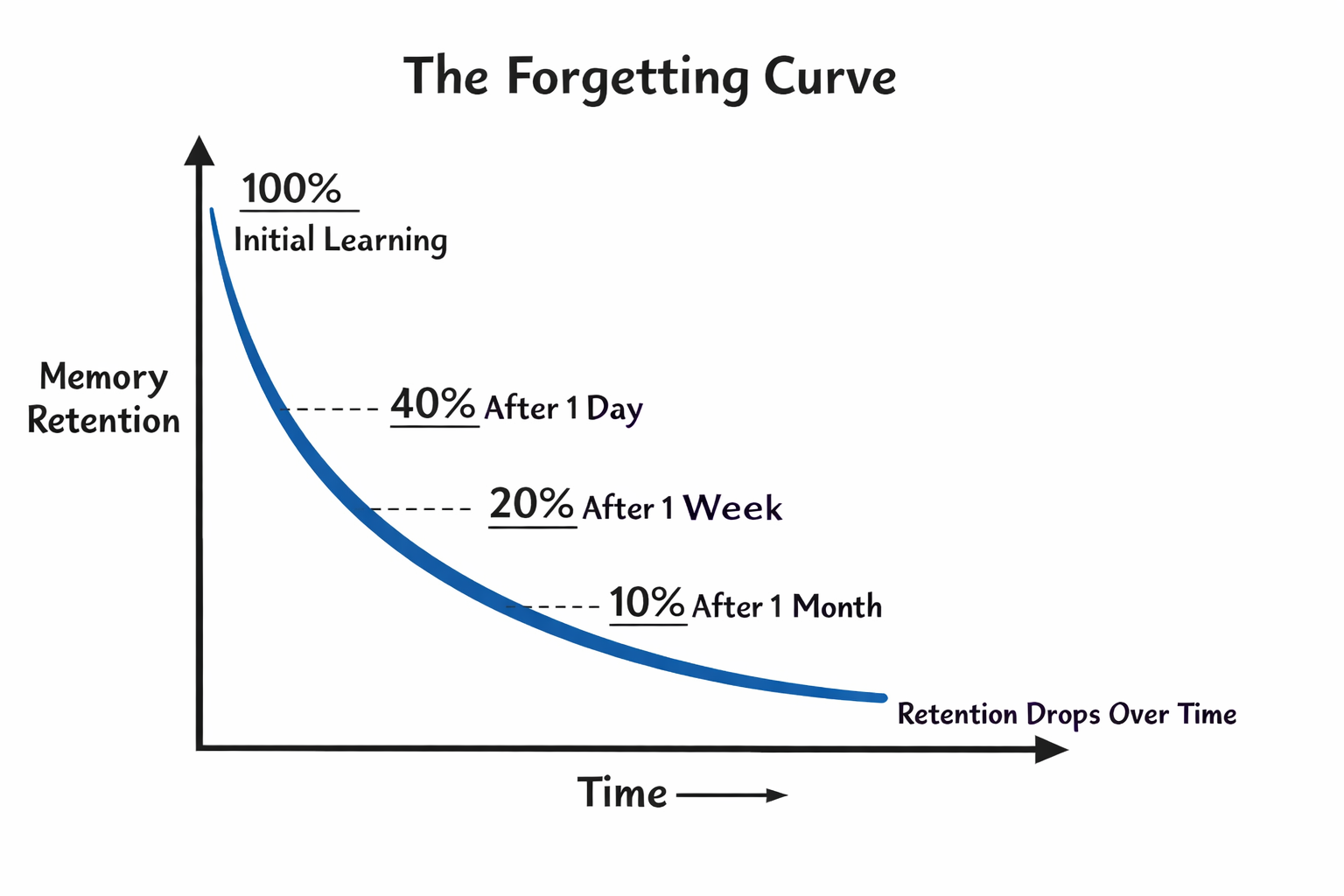

The Forgetting Curve

Information is lost over time to the Forgetting Curve. There’s a certain strength or durability of recall for anything you could remember, and that strength depends on several factors:

- how difficult the underlying material is

- how much the information emotionally resonates with you

- how well it connects to things you already know

- how much sleep you got, or how stressed you are

- whether you actively engaged with it or passively absorbed it

Note: Percentages are illustrative only. Actual retention rates vary widely based on the factors above.

Note: Percentages are illustrative only. Actual retention rates vary widely based on the factors above.

Personally (and probably for all of us), meaningful information sticks easiest. If I find myself excited about a topic, it’s easier to recall pieces of that information.

For whatever the information though, it’s quickly forgotten if you never try to recall it.

… the greatest drop in information retention occurs just after the new information is initially introduced. That is to say, data gathered while listening to a lecture or reading a chapter is often lost within a few hours or days of leaving the lecture hall or closing the book. By the end of the week, 90% of that material is gone. — Spaced Effect Learning and Blunting the Forgetfulness Curve

That 90% figure isn’t universal. Emotionally charged memories, personally meaningful information, and things connected to existing knowledge all decay slower. But the pattern holds: without reinforcement, most information fades faster than we’d like to admit.

But here’s the good news: the curve has a weakness. Every time you actively recall something (not re-read), the decay slows. The memory becomes more durable. Space those recalls out optimally, and you maintain knowledge with surprisingly little effort.

Depth of knowledge

Related to recalling information, we’re very good at thinking we know something but we really only have surface knowledge. This is described as the illusion of explanatory depth, and it’s important to keep in mind when you think about what you want to understand in the world. We’re very good at fooling ourselves, and there’s no cognitive bias repeated more these days than the Dunning-Kruger effect.

We easily fool ourselves into thinking we understand, and life goes on. We don’t realize this until we’re confronted with a situation that requires deeper understanding.

For example: Do you really understand how tax brackets work? Some people say yes until they get a raise and worry it will “push them into a higher bracket.” They don’t realize only the income above that threshold is taxed at the higher rate, and that misunderstanding quietly shapes career decisions, negotiations, and financial anxiety for years.

Forcing yourself to actively recall something, not just re-read it or nod along, exposes the gaps. When you try to explain an idea and fail, the illusion shatters. You discover exactly where your understanding breaks down. That’s uncomfortable, but it’s the first step toward actually knowing something.

So the path forward involves two distinct problems: building real understanding in the first place, and then retaining it over time. Most people only think about the first. But even hard-won knowledge fades if you never revisit it.

Why learn anything?

Personal Enjoyment and Growth

Learning feels good when it actually works. Not the fake satisfaction of highlighting a textbook, but the real hit when a concept clicks and you can use it. That feeling is addictive, and it only happens when you genuinely understand something. If learning has always felt like a chore, consider that the method was broken, not your motivation.

Credibility and Trust

People can tell when you’re faking it. Not always immediately, but follow-up questions expose shallow knowledge fast. The person who can answer the second and third question, who can explain why and not just what, earns trust. The person who deflects or changes the subject doesn’t.

Better Decision Making

Real knowledge means having the right information when it matters. Instead of vague feelings or frantically Googling basics, you pull from a mental library. Better judgment leads to fewer mistakes leads to increased confidence.

Compounding Knowledge

Learning speeds up when you have a foundation. Each concept becomes a hook for related ideas. Just like compound interest, you realize gains later that come from earlier investments.

Creativity

Creative leaps happen when you see a connection nobody else does. But you can’t connect dots you don’t have. The more concepts you genuinely understand, the more raw material your brain has to work with. Every domain you learn gives you a new lens for the others.

Fact-Checking

When you actually understand something, you can smell bullshit. Misinformation and disinformation rely on surface-level knowledge. Deep understanding gives you a built-in filter.

Even with GenAI?

If you can ask Chat anything, why bother memorizing?

-

Speed matters. In a conversation, a meeting, or a debugging session, the person who can think fluidly without reaching for a tool has an advantage. Knowledge in your head is latency-free.

-

You can’t prompt for what you don’t know exists. AI is great at answering questions, but you have to know which questions to ask. The more you know → the better your prompts → the more useful the output. Ignorance compounds in the other direction too.

-

AI makes confident mistakes. Hallucinations are real, and they’re hardest to catch when you lack the background to recognize them. Your knowledge is your error-detection layer.

-

Thinking requires material. You synthesize, connect, and reason with facts. AI can help, but it can’t do your thinking for you. The richer your mental library, the more interesting the thoughts you can have.

GenAI is a powerful tool. But tools amplify what you bring to them. The more you know, the more useful they become.

So what actually works?

We forget quickly, we fool ourselves about what we know, and we want the benefits of deep understanding. What do we do about it?

- Re-reading feels productive but is mostly passive. You’re not testing yourself.

- Note-taking helps encoding but doesn’t address the forgetting curve.

- Cramming works short-term but decays rapidly.

The answer is to exploit the forgetting curve’s weakness: active recall at strategic intervals.

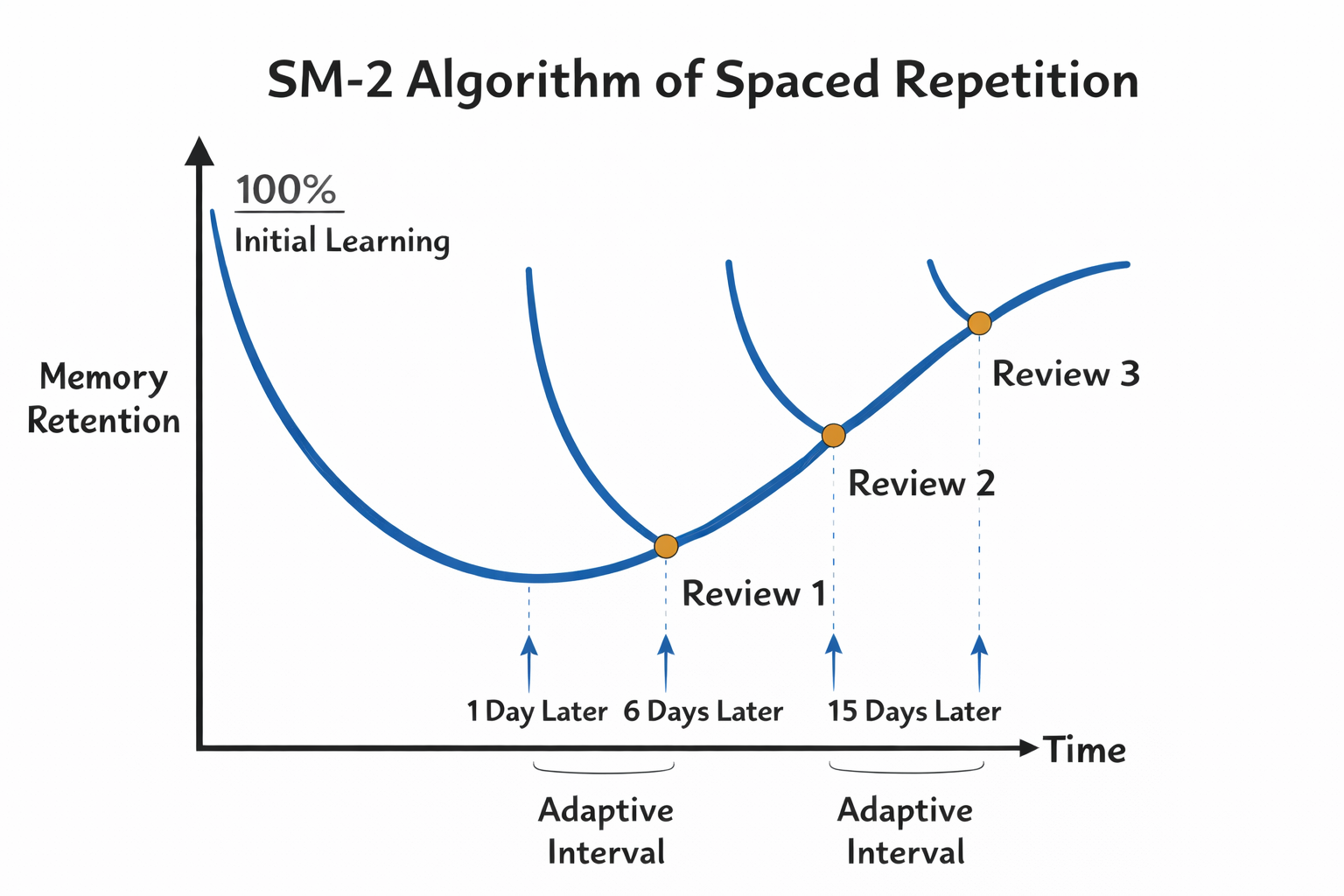

Spaced Repetition

Spaced-repetition is the most widely understood way of making sure the things you want to stay in your head, do, with the least number of check-ins.

- Cramming before you need it isn’t optimal (especially on little sleep)

- Studying every day is wasteful

- Reviewing without a system to manage it for you is unreliable

Note: This is a simplified illustration of the SM-2 algorithm used by Anki. Actual intervals depend on your performance ratings.

Note: This is a simplified illustration of the SM-2 algorithm used by Anki. Actual intervals depend on your performance ratings.

What it won’t do

Flashcards are great for retention, but they’re not a substitute for understanding. Critics rightly point out that you can drill facts without ever grasping the deeper connections. Spaced repetition works best when:

- You’ve already understood the material and want to keep it accessible

- The knowledge is discrete and can be atomized (dates, vocabulary, syntax)

- You combine it with actual practice: use the knowledge in real contexts

What to remember?

There’s an infinite world of things to remember, so consider:

- birthdays, anniversaries, and phone numbers

- vocab, 2nd language learning, music theory

- scientific facts, theories

- ethical/moral frameworks, logical fallacies

- concepts for school and certification

- keyboard shortcuts, programming language syntax, system design patterns

- CPR concepts or how to jump start your car battery

- political terms or how to reframing arguments

- historical dates and events

If you’re trying to learn something complex (like how to debug a distributed system), flashcards alone won’t get you there. Use them to retain the building blocks. Build understanding through projects and practice.

But for having a system for the retension piece, Anki is the solution.

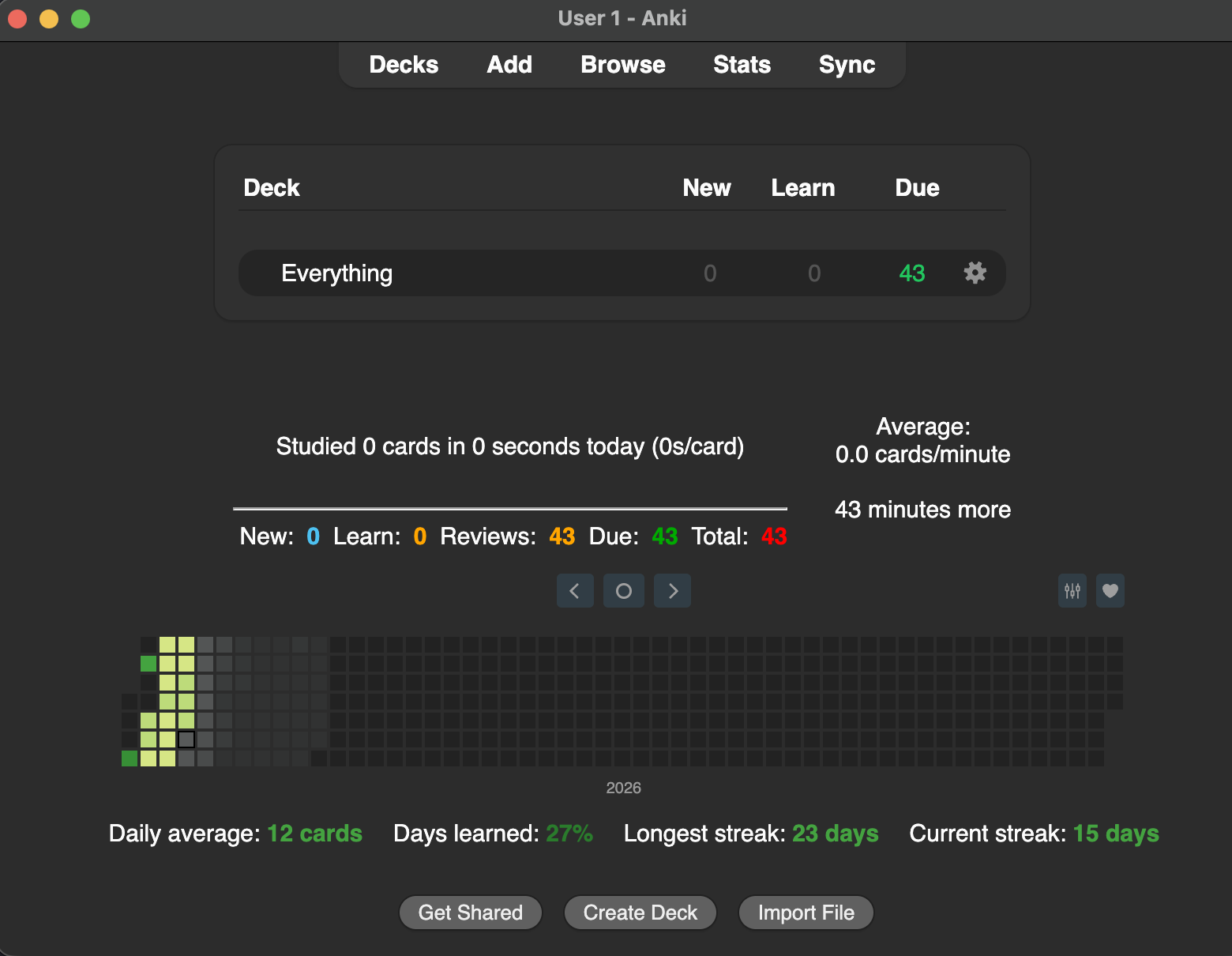

Why Anki?

Anki is the most popular spaced-repetition system. Students use it to prepare for tests. Doctors use it to remember medical training. Software developers (hi!) use it to remember syntax and design concepts.

What does it look like?

Below is an example, customized using addons mentioned later in this post:

Reviewing a note would look something like this:

There’s a whole Anki manual for how to understand and use Anki, but I’ll admit I’ve never gone through it. It’s pretty intuitive.

You may want to check on card types and styling. Or if you want to get fancy, there’s add-ons to extend Anki’s functionality.

Anki’s been around since 2006, and it’s the de-facto app for spaced repetition. If there’s something you want to study, someone has figured out how to do it.

Why not Anki?

I’ll quickly take a moment to say why Anki might not be for you:

- It takes time to set up, and to set it up well (especially if you go beyond basic cards)

- Depending on the concepts you care about, it might not be easy to break them down into atomic pieces

- It can feel like a chore so if you don’t need another obligation in your life, maybe it’s not for you

- If you prefer pen and paper

- You don’t want to improve (but I think I ruled those people out already)

Alternatives include Thought Saver, Memrise, Quizlet, and Brainscape. Others might be found here.

How to create notes?

One of the major barriers to getting started is getting the information you want added to Anki. Keep this simple. You can also find shared decks to get started quickly.

A quick note on Premade vs. Homemade decks:

- Shared decks might be good if you have a specific certification or test to prepare for

- Homemade decks are probably better in most cases because you want to be intentional about what you want to remember

I started by having a few different decks, but I’ve since settled on one called Everything. Use tags to have any sort of organization.

- Remove the choice: Put every card in a single deck

- Some evidence suggests interleaving subjects is useful in the memorization process (though maybe only when close in relation)

- Add groups of cards every day or every few days

- Anki + Obsidian + Git to version control your notes and keep linked with other learning

Tools

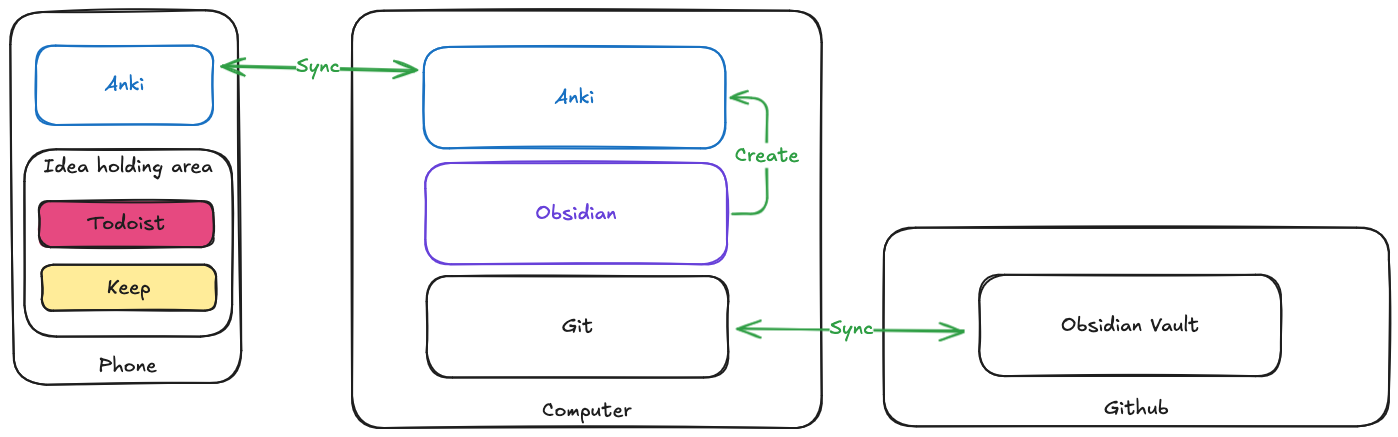

If you’re more tech savvy, you might consider combining tools to make note creation easier. The following is my setup.

I’ve made creating notes a ritual I do in one place (laptop) with a few tools. If I only have my phone, I add notes about what I want to learn to apps like Todoist or Google Keep.

When I get back to my laptop, I use the following tools:

- Obsidian with the Obsidian_to_Anki plugin

- Anki with AnkiConnect (see Obsidian_to_Anki guide)

- Git for version control, using the Obsidian Git plugin

- GenAI for generating cards - I paste the format of what Obsidian_to_Anki expects and have GenAI make cards in a domain fitting that format

The downside of only adding cards from my laptop is if I’m out and have an idea for a card, I don’t immediately get it into Anki from my phone. The benefit is I’m being methodical in my process and intentional about what to remember.

Why Obsidian?

Obsidian is already where I keep my notes, so it made sense to create Anki cards there too. But there’s a more important reason: my cards live in plain markdown files that I own, not locked inside Anki’s database. If Anki changes, dies, or I switch tools, my source material survives. The cards are the output; the notes are the source of truth.

Obsidian also lets me link cards to related notes in my vault. A card about remembering which projects I’ve completed for my career and how they map to cultural questions in an interview can link to the actual project notes. When I review a card and realize I need more context, I can jump straight to my notes instead of starting from scratch.

Why Git?

I treat my vault like any other software project. Version control means I can see what I’ve added, when, and roll back mistakes. It also means my notes are backed up to a remote repository automatically, allowing me to share my Obsidian vault + Anki card generation setup to my other devices.

GenAI

If you have a lot of cards to make on a subject or need ideas, your favorite GenAI tool can help.

Just remember:

- Make sure the answer is correct! You don’t want to learn the wrong thing.

- Be intentional about reframing the questions, answers, and formatting to fit your learning goals.

- Re-prompt until you get what you want.

Example prompt to GenAI, replacing the last statement with whatever topic I want cards for:

Below is the format for building anki cards in Obsidian.

START

Basic

Question here

Back:

```language_here

code here

```

Tags: general_topic_here programming_language_here

END

For example, a real card might be below.

START

Basic

How do you reverse s: &str in rust?

Back:

```rust

s.chars().rev().collect()

```

Tags: software rust

END

Or with cloze replacement

START

Cloze

To connect to a Postgres instance, use: {{c6::{{c1::psql}} {{c2::-h HOST}} {{c3::-p PORT}} {{c4::-U DB_USER}} {{c5::DB_NAME}}}}

Tags: software postgres

END

Based on this, create me atomic Anki cards for learning the planets in the solar system.

And the output will be something like the following, which I can paste directly into Obsidian (cmd+shift+v to paste without formatting):

START

Basic

What is the order of the planets from the Sun?

Back:

Mercury → Venus → Earth → Mars → Jupiter → Saturn → Uranus → Neptune

Tags: science astronomy

END

START

Basic

Which planet is closest to the Sun?

Back:

Mercury

Tags: science astronomy

END

Organization

- Use an Obsidian directory called Anki where the Obsidian_to_Anki plugin is configured to scan

- All cards go to the

Everythingdeck, so configure this setting in the plugin - Inside of the Anki directory in Obsidian, I make files to organize topics and make it easier to find where I created a card

- Inside each file, I use typical markdown headings to organize notes further, with each card following the format above

Workflow

- Open and sync Anki on my laptop

- Add cards to Obsidian

- Run the

Obsidian_to_Anki: Scan Vaultcommand to send all my updates into Anki - Sync Anki again

- Open my phone, sync, and run through my cards

What’s a good note?

You want to get through each card quickly. Don’t make large, multi-step processes as a card. I have a few cards that are a list of a few items, but that’s the exception to the rule.

Some things to keep in mind:

- Cards should be single atomic concepts

- Use

clozeto turn one card into many notes, studying concepts by name or description - Notes should prompt you as you would be prompted when you want the information available

Bad cards

Too broad:

Q: Explain how the immune system works.

This requires a lecture, not a flashcard. You’ll either give a shallow answer or spend five minutes reciting paragraphs. Neither helps retention.

Multiple concepts crammed together:

Q: What are the three branches of the US government and what does each do?

If you forget one, the whole card fails. Split it into separate cards.

Vague or ambiguous:

Q: What is important about sleep?

Important for what? Memory? Health? Performance? You’ll answer differently each time, which defeats the point.

Good cards

Atomic and specific:

Q: What type of white blood cell attacks infected cells directly?

A: T cells (specifically cytotoxic T cells)

One concept. One answer. Fast to review.

Single concept:

Q: What branch of the US government interprets laws?

A: Judicial

Split the original into three cards. Now forgetting one doesn’t fail the whole thing.

Clear and unambiguous:

Q: How many hours of sleep do most adults need for optimal cognitive function?

A: 7-9 hours

The question specifies what aspect of sleep and what outcome. You’ll answer the same way every time.

Cloze for related facts:

{{c1::Melatonin}} is the hormone that regulates {{c2::sleep-wake cycles}}.

One card, two reviews. You learn the concept from both directions.

Prompted like real life:

Q: Your teammate says they’re blocked but won’t ask for help. What’s a good first question to ask?

A: “What have you tried so far?”

This mirrors how you’d actually need the information. The prompt matches the trigger.

How to study?

Remember you’re trying to learn things, not fool yourself into thinking you got something right that you didn’t. If you’re spending too much time on a card, it might be a poorly designed card. If you’re avoiding your deck because it’s uninteresting, introspect on why you’re trying to learn these concepts to begin with.

- Be rigorous about the ratings. Don’t fool yourself (you’re the easiest one to fool).

- Use Good/Hard/Again ratings, but stay away from Easy (at least early on). More repetition in the short term is helpful.

- Build a habit to go through deck instead of pulling up another app

- “When I sit down, I’ll do my Anki cards”

- “If I don’t have any, I’ll think about what’s next to add”

- Suspend cards that are too much cognitive load. Look to simplify at a later time.

- Use an Anki widget and put it on your home screen. It’ll display when there are new cards to review.

After a few days, it might take you 6 minutes to refresh 40 cards and stave off forgetting for weeks or months. That’s a great investment.

Anki Mods

Card templates

Because we are putting everything in the same deck, it’s useful to ensure tags show in your prompt.

Enable this format by doing the following (modifying as you see fit):

- Tools → Manage Note Types → Basic → Cards

- Tools → Manage Note Types → Cloze → Cards

Basic Front:

{{Front}}<br><br>

Tags: {{Tags}}

Basic Back:

{{FrontSide}}

<hr id=answer>

{{Back}}

Cloze Front:

{{cloze:Text}}<br><br>

Tags: {{Tags}}

Cloze Back:

{{cloze:Text}}<br>

{{Back Extra}}

Add-ons

The add-ons I use (and any settings I have configured) include:

{

"contextmenu_show_copy_url": true,

"contextmenu_show_open_in_browser": true,

"contextmenu_show_set_link_text": true,

"contextmenu_show_transform_selected_url_to_hyperlink": true,

"contextmenu_show_unlink": true,

"encode_illegal_characters_in_links": true,

"guess and auto fill fields in dialog from clipboard": true,

"prepend incomplete url default": "http",

"remove whitespace from beginning and end of urls": true,

"shortcut_insert_link": "Ctrl+Shift+H",

"shortcut_unlink": "Ctrl+Shift+Alt+H",

"show_in_reviewer_context_menu": true,

"unlink_button_and_shortcut": true

}

{

"apiKey": null,

"apiLogPath": null,

"ignoreOriginList": [],

"webBindAddress": "127.0.0.1",

"webBindPort": 8765,

"webCorsOrigin": "http://localhost",

"webCorsOriginList": [

"http://localhost",

"app://obsidian.md"

]

}

{

"Separator": "::"

}

- Edit Field During Review Cloze

- Image Occlusion Enhanced

- Markdown and KaTex Support

- More Decks Stats and Time Left

{

"CountTimesNew": 2,

"DaysToConsider": 1,

"LearnColorDark": "Orange",

"LearnColorLight": "Red",

"NewColorDark": "#4DC1F1",

"NewColorLight": "Blue",

"ReviewColorDark": "Orange",

"ReviewColorLight": "Red",

"ShowTimeLeft": true,

"TotalColorDark": "Red",

"TotalColorLight": "Grey",

"TotalDueColorDark": "#00AA00",

"TotalDueColorLight": "#00AA00"

}

{

"settings": [

{

"configs": {

"answer_fld": "Answer",

"choice_fld": "Choices",

"n_choice": "3",

"question_fld": "Question",

"r_choice_fld": "Reversed Choices",

"reversed": false

},

"name": "Default",

"notetype": "Multiple Choice (optional reversed card)"

}

]

}

{

"hotkey": "Alt+s",

"limitToLangs": [

"Rust",

"Python",

"Go",

"Bash",

"TOML"

],

"style": "dracula"

}

Share Your Knowledge

Ok, so you know what you want to know and you’re using Anki to remember it. You’re going to use it to expand your knowledge over time, come up with new abstractions, and generally be a more informed person.

Why not share what you know?

One good way to do this is to learn by teaching, and use the Feynman Technique.

- Study a concept

- Explain it to an imaginary child (as brief as possible)

- Identify gaps

- Refine (repeat steps)

Combining this with Anki, let’s say I want to learn about Kubernetes.

- I make cards about simple concepts like “What is a DaemonSet?” or “What can run in a Pod?”

- I review these cards over time until I feel comfortable with the concepts

- I try to explain Kubernetes to an imaginary person, and realize I don’t understand how networking works

- I make more cards about networking in Kubernetes, review them, and try again

At some point in this process you might replace the imaginary person with a real person. Maybe you write a blog post, make a video, or just explain it to a friend. In these instances you’ll find gaps you didn’t know you had, and you’ll be able to make note of this and start your learning cycle again.

Takeaways

You will forget almost everything you learn. That’s not a personal failing; it’s how memory works. The only question is whether you accept it or do something about it.

Spaced repetition isn’t magic. It’s just forcing yourself to recall information at the right intervals before it fades. Anki automates the scheduling so you don’t have to think about it. A few minutes a day keeps years of learning accessible.

The hard part isn’t the tool. It’s deciding what matters enough to remember, writing cards that actually test understanding, and showing up daily. Start small. Pick one thing you’re learning right now and make five cards. Review them tomorrow. See if it sticks.

And when you think you know something, try explaining it. Teaching exposes what you’ve actually learned versus what you’ve merely reviewed. The gaps you discover become your next cards.

So, what are you going to learn next?